The medical profession primarily views pain as a consequence of an inflammatory problem (1, 2, 3, 4). With the realization that inflammation, for the most part, is a chemical event, focus on the inflammatory chemistry of pain has become a priority of drug companies and for the physicians that prescribe their products. Often these efforts target inflammatory eicosanoids (prostaglandins, leukotrienes, etc.) and/or inflammatory cytokines (interleukins) (5, 6).

However, a huge problem attributed to the use of anti-inflammatory chemistry drugs for chronic pain has been documented: these drugs are toxic, and their regular use causes significant health problems and even death. A few examples include:

KIDNEY DAMAGE

Risk of Kidney Failure Associated with the Use of Acetaminophen, Aspirin, and Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs:

New England Journal of Medicine; December 22, 1994 (7)

GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Gastrointestinal Toxicity of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs:

The New England Journal of Medicine; June 17, 1999 (8)

HEART ATTACK / STROKE

NSAID Use and the Risk of Hospitalization for First Myocardial Infarction in the General Population:

European Heart Journal; May 26, 2006 (9)

Cardiovascular Safety of Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

British Medical Journal; January 11, 2011 (10)

Editorial: Cardiovascular Safety of NSAIDs

British Medical Journal; January 11, 2011 (11)

Duration of Treatment with Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Impact on Risk of Death and Recurrent Myocardial Infarction in Patients with Prior Myocardial Infarction:

Circulation; May 21, 2011 (12)

Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs and the Risk of Atrial Fibrillation:

British Medical Journal Open; April 8, 2014 (13)

DEMENTIA / ALZHEIMER’S

Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease with Prior Exposure to NSAIDs in an Elderly Community-based Cohort:

Neurology; June 2, 2009 (14)

HEARING LOSS

Analgesic Use and the Risk of Hearing Loss in Men:

The American Journal of Medicine; March 2010 (15)

ERECTILE DYSFUNCTION

Regular Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Use and Erectile Dysfunction:

Journal of Urology; April 2011 (16)

Ibuprofen Alters Human Testicular Physiology to Produce a State of Compensated Hypogonadism:

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences; January 23, 2018 (17)

SURGICAL HEALING

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs in the Acute Post-operative Period Are Associated with an Increased Incidence of Pseudarthrosis, Hardware Failure, and Revision Surgery Following Single-level Spinal Fusion:

Spine; August 1, 2023 (18)

AUTISM

Prenatal and Postnatal Exposure to Acetaminophen in Relation to Autism Spectrum and Attention?deficit and Hyperactivity Symptoms in Childhood:

Meta?analysis in Six European Population?based Cohorts:

European Journal of Epidemiology; October 2021 (19)

Paracetamol [acetaminophen] Use During Pregnancy: A Call for Precautionary Action:

Nature Reviews Endocrinology; December 2021; (20)

A Systematic Review of the Link Between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Acetaminophen: A Mystery to Resolve:

Cureus; July 18, 2022 (21)

In 2003, an article published in the journal Spine stated (22):

“There is insufficient evidence for the use of NSAIDs to manage chronic low back pain.”

“Gastrointestinal toxicity induced by NSAIDs is one of the most common serious adverse drug events in the industrialized world.”

In 2006, an article published in the journal Surgical Neurology stated (23):

“The use of NSAID medications is a well-established effective therapy for both acute and chronic nonspecific neck and back pain.”

“Extreme complications, including gastric ulcers, bleeding, myocardial infarction, and even deaths, are associated with their use.”

“More than 70 million NSAID prescriptions are written each year, and 30 billion over-the-counter NSAID tablets are sold annually.”

“5% to 10% of the adult US population and approximately 14% of the elderly routinely use NSAIDs for pain control.”

“Selling NSAIDs is a multibillion-dollar industry.”

“Almost all patients who take the long-term NSAIDs will have gastric hemorrhage, 50% will have dyspepsia, 8% to 20% will have gastric ulceration, 3% of patients develop serious gastrointestinal side effects, which results in more than 100,000 hospitalizations, an estimated 16,500 deaths.”

“NSAIDs are the most common cause of drug-related morbidity and mortality reported to the FDA and other regulatory agencies around the world.”

“[One author referred to the] chronic systemic use of NSAIDs to ‘carpet-bombing,’ with attendant collateral end-stage damage to human organs.”

Historically, chiropractic care primarily targets mechanical pain. As the name suggests, mechanical pain is pain that is primarily mechanical in nature rather than inflammatory in nature. A common metaphor is the pain associated with having one’s finger caught in a slammed door. The best solution for this mechanical pain is not the consumption of a pain drug, but rather for someone to mechanically open the door, releasing the finger. Chiropractic mechanical based care (spinal manipulation, or specific line-of-drive adjustments) is common and successful for mechanical-based pain syndromes, with high levels of patient satisfaction (24, 25). In fact, a recent study (October 2023) documented that chiropractic care was the most commonly chosen care by patients suffering from new-onset neck pain (26).

With advances in the understanding of spine pain syndromes, it became understood that there was an overlap between mechanical pain and chemical-inflammatory pain; as different as these etiologies for these two types of pain are, they often co-exist.

An early example of this understanding was published by Vert Mooney, MD, from the University of California, San Diego. When Dr. Mooney was the president of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine, his Presidential Address emphasized the relationship between mechanical pain and chemical-inflammatory pain. His address was published in the journal Spine, and titled (27).

Where Is the Pain Coming From?

Wound healing results in scar (fibrosis) formation which is less functional than the original tissue. Yet, early mobilization reduces scarring and enhances recovery.

Dr. Mooney notes that spinal healing and spinal degenerative disease create spinal stiffness. Spinal stiffness has the greatest impact on the chemistry of the intervertebral disc because the disc is avascular. It is difficult to disperse any inflammatory chemicals that accumulate within the disc because of its lack of blood supply, especially in the presence of spinal stiffness. Dr. Mooney explains these concepts as follows:

“Mechanical events can be translated into chemical events related to pain.”

“The fluid content of the disk can be changed by mechanical activity.”

“Mechanical activity has a great deal to do with the exchange of water and oxygen concentration [in the disk].”

An important aspect of disk nutrition and health is the mechanical aspects of the disk related to the fluid mechanics.

The pumping action maintains the nutrition and biomechanical function of the intervertebral disk.

“Research substantiates the view that unchanging posture, as a result of constant pressure such as standing, sitting or lying, leads to an interruption of pressure-dependent transfer of liquid. Actually, the human intervertebral disk lives because of movement.”

“In summary, what is the answer to the question of where is the pain coming from in the chronic low-back pain patient? I believe its source, ultimately, is in the disk. Basic studies and clinical experience suggest that mechanical therapy is the most rational approach to relief of this painful condition.”

“Prolonged rest and passive physical therapy modalities no longer have a place in the treatment of the chronic problem.”

The relationship between mechanical pain and chemical-inflammatory pain was significantly advanced by Manohar M. Panjabi, PhD, from Yale University School of Medicine. Dr. Panjabi explained his hypothesis in the European Spine Journal in 2006 in an article titled (28):

A Hypothesis of Chronic Back Pain:

Ligament Sub-failure Injuries Lead to Muscle Control Dysfunction

Dr. Panjabi understands that a sub-failure injury of the spinal ligament is an injury caused by stretching of the tissue beyond its physiological limit, but less than to its failure point. These sub-failure injuries of ligaments are incomplete injuries, often tearing only a few fibers. These sub-failure injuries to ligaments “disrupt and/or injure the embedded mechanoreceptors.”

Injured muscles heal relatively quickly due to abundant blood supply and therefore are not the main cause of chronic back pain. In contrast, ligament injuries heal poorly and therefore lead to tissue degeneration over time. Tissue degeneration further causes aberrant mechanical function, resulting in tissue stress, inflammation, and pain. Dr. Panjabi notes:

“Abnormal mechanics of the spinal column has been hypothesized to lead to back pain via nociceptive sensors.”

“The role played by the injury to the mechanoreceptors embedded in the ligaments of the spinal column has not been explored by any hypothesis.”

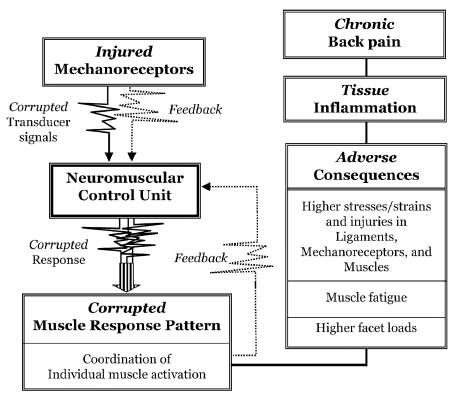

A summary of Dr. Panjabi’s hypothesis is presented below:

Dr. Panjabi’s Explanation

“The injured mechanoreceptors send out corrupted transducer signals to the neuromuscular control unit, which finds spatial and temporal mismatch between the expected and received transducer signals, and, as a result, there is muscle system dysfunction and corrupted muscle response pattern is generated.”

“Consequently, there are adverse consequences: higher stresses, strains, and even injuries, in the ligaments, mechanoreceptors, and muscles.”

“There may also be muscle fatigue, and excessive facet loads.”

“These abnormal conditions produce neural and ligament inflammation, and over time, chronic back pain.”

In 2011, Nikolai Bogduk, MD, PhD, presented a paper in the journal Spine, titled (29):

On Cervical Zygapophysial Joint Pain After Whiplash

Nikolai Bogduk is a unique individual. As of December 2023, PUBMED, the search engine for the U.S. National Library of Medicine, locates 306 articles using his name. Dr. Bogduk is Emeritus Professor of Pain Medicine at the University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia. Dr. Bogduk holds an MD, PhD, and ScD. He began his research into spinal pain in 1972. Presently, Dr. Bogduk is the most noted, respected, and influential clinical anatomist of our time, and perhaps of all history.

In this article, Dr. Bogduk explains the mechanism of rear-end collision “whiplash” injuries. He notes that the cervical spine undergoes a “highly abnormal” “S” shaped deformation with extension of the lower cervical spine and flexion of the upper cervical spine. This abnormal mechanical configuration primarily injures the facet joints.

Dr. Bogduk presents the “convergent validity” mechanistic evidence that implicates the cervical facet joints as the leading source of chronic neck pain after whiplash. He reviews data from:

- Whiplash postmortem studies

- Whiplash biomechanics studies

- Whiplash clinical studies

In his explanations, Dr. Bogduk references the mechanical work of Dr. Panjabi. In other words, he is looking at the mechanical explanation for chronic whiplash pain.

In 2021, an article was published in the journal Pain Medicine, titled (30):

The Prevalence of “Pure” Lumbar Zygapophysial Joint Pain in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain

In this study, the authors use zygapophysial joint (Z joint) synonymously for facet joint. Two hundred and six patients with possible lumbar facet joint pain underwent controlled diagnostic blocks to determine the prevalence of “pure” lumbar facet joint pain. All patients attributed their back pain to some form of injury. The authors note:

Prior studies indicate that the joints that are most often painful are L4–L5 and L5–S1. This finding was confirmed in this study.

“The prevalence of ‘pure’ lumbar Z joint pain was 15% (10–20%).”

It is relevant to acknowledge that chiropractic spinal adjustments primarily influence the facet (Z) joints. It is also important to know that 63% of patients who seek chiropractic care do so for the management of chronic back pain (25).

In 2017, a study from researchers at the University of Pennsylvania published a study in the Journal of Biomechanical Engineering, titled (31):

The Interface of Mechanics and Nociception in Joint Pathophysiology

This study reviews the mechanical, chemical, and neurological mechanisms contributing to synovial joint pain. The authors note that chronic joint pain is a widespread problem that frequently occurs with aging and trauma. The authors emphasize the importance of the mechanical pain model by stating:

General Concepts

“Synovial joints permit complex motion and often sustain loads several times greater than the weight of the human body.”

“Repeated mechanical loading above the normal physiological conditions contribute to the initiation of acute tissue damage and degeneration.”

“Trauma and repeated loading can induce structural and biochemical changes in joints, altering their microenvironment and modifying the biomechanics of their constitutive tissues, which themselves are innervated.”

“Peripheral pain sensors can become activated in response to changes in the joint microenvironment and relay pain signals to the spinal cord and brain where pain is processed and perceived.”

“The local mechanical environment of joints can be substantially altered after injury or degeneration, which can produce dysfunctional nociceptive signaling.”

“Innervated by mechanoreceptors, disruption of the collagen fibers that make up the facet capsular ligament can initiate nociceptive signaling and lead to both acute and chronic pain.”

“Both traumatic and repeated mechanical disruption can induce structural changes to joint tissues and inflammatory cascades, which separately activate pain fibers via a modified biomechanical and biochemical environment.”

“These changes in neuronal signaling can lead to persistent pain even in the absence of any on-going tissue damage or input from peripheral nociceptive fibers.”

“The facet capsular ligament is innervated by mechanoreceptors that encode movement and stretch, and also by nociceptors that encode nociceptive stimuli.”

“Disruption of the facet capsule and other innervated tissues in the facet joint can elicit pain.”

“Excessive stretch of the facet capsular ligament induces persistent pain and modifications in neuronal signaling.”

“[Complete facet capsule rupture] does not initiate chronic pain, [but it can lead to] long-term alterations in the mechanical properties of that joint due to tissue scarring and/or degenerative cascades.”

“Mechanical loading exceeding the physiologic range of a given joint can lead to persistent pain that arises from many structures in that joint.”

Degenerated Joints

Degenerative joint pathologies, such as OA, are initiated by a combination of applied mechanical loads and biological cascades within the joints’ tissues.

Both trauma and age contribute to joint degeneration.

“Degenerated joint tissues respond differently to loading than healthy counter-parts.”

Degenerated joint tissues have lower thresholds for mechanical injury.

Joint degeneration alters the biomechanical environment of innervated joint tissues, lowering thresholds for painful injury.

Joint degeneration changes joint biomechanics, inflammatory status, and pain, and increases nociceptive signaling.

The Cervical Spine

“In the neck, the facet capsular ligament is particularly vulnerable to excessive spinal motions because of the potential for ligament stretch to activate the nociceptors innervating that ligament.”

“Neck pain is most often induced by trauma and can involve damage, like loading and stretching of the facet capsular ligament, to the bilateral facet joints that provide articulations between spinal levels.”

Neck trauma can produce peak strains in the C6/C7 facet capsule, sufficient to produce localized altered collagen fiber kinematics and sustained pain.

Physiologic strains of 10–15% only activate mechanoreceptors, whereas strains greater than 25% produce sustained nociceptive “after-discharge,” and induce morphological changes in axons, including local swelling.

“Facet joint …. pain syndromes are complex disorders with mechanical, molecular, and nociceptive contributors.”

Large modulation in the biomechanics of joints may not be required for pain to be initiated, “especially if there are altered joint kinematics.”

“This may explain why patients who undergo moderate loading of the neck develop persistent pain symptoms.”

This study, in particular, emphasizes the relationship between altered mechanical function, the accumulation of inflammatory chemicals, and the genesis of pain syndromes. It is very supportive of the models that are taught in chiropractic education and used in chiropractic clinical practice. It explains the benefits and necessity for mechanical-based care for the management of pain syndromes.

SUMMARY

An ongoing theme from the studies presented here is that inflammatory chemicals increase the incidence of pain. Traditional medical practice often uses anti-inflammatory drugs to help people with pain syndromes, but frequently these drugs are not very effective and they are associated with many dangerous side-effects, including death, especially if chronically consumed.

Patients with unresolved spinal pain syndromes often shop for alternatives in an effort to be helped. The top alternative with good outcomes, low costs, high patient satisfaction, long-term benefits, and an extremely high safety profile is chiropractic care (22, 32, 33, 26, 34, 35). An explanation for these outcomes, supported here, is that ongoing inflammation and pain can be driven by aberrant mechanical function. Chiropractic care targets the aberrant mechanical function with spinal adjusting and follow-ups, like exercise. This reduces both inflammation and pain.

REFERENCES

- Omoigui S; The Biochemical Origin of Pain; S.O.T.A. Technologies, Inc.; Hawthorne, CA; 2003.

- Omoigui S; The Biochemical Origin of Pain: The Origin of All Pain is Inflammation and the Inflammatory Response: Inflammatory Profile of Pain Syndromes; Medical Hypothesis; 2007; Vol. 69; No. 6; pp. 1169–1178.

- Foreman J; A Nation in Pain; Healing Our Biggest Health Problem; Oxford University Press; 2014.

- Zhang Q, Bang S, Chandra S, Ji RR; Inflammation and Infection in Pain and the Role of GPR37; International Journal of Molecular Science; November 20, 2022; Vol. 23; No. 22; Article 14426.

- Kang JD, Georgescu HI, McIntyre-Larkin L, Stefanovic-Racic M, Donaldson WF, Evans CH; Herniated Lumbar Intervertebral Discs Spontaneously Produce Matrix Metalloproteinases, Nitric Oxide, Interleukin-6, and Prostaglandin E2; Spine; February 1, 1996; Vol. 21; No. 3; pp. 271-277.

- Kang JD , Stefanovic-Racic M, McIntyre LA, Georgescu HI, Evans CH; Toward a Biochemical Understanding of Human Intervertebral Disc Degeneration and Herniation: Contributions of Nitric Oxide, Interleukins, Prostaglandin E2, and Matrix Metalloproteinases; Spine; May 15, 1997; Vol. 22; No. 10; pp 1065-1073.

- Perneger TV, Whelton PK, Klag MJ; Risk of Kidney Failure Associated with the use of Acetaminophen, Aspirin, and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs; New England Journal of Medicine; December 22, 1994; Vol. 331; No. 25; pp. 1675-1679.

- Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G; Gastrointestinal Toxicity of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs; New England Journal of Medicine; June 17, 1999; Vol. 340; No. 24; pp. 1888-1899.

- Helin-Salmivaara A, Virtanen A, Vesalainen R, Gronroos JM, Klaukka T, Idanpaan-Heikkila JE, Huupponen R; NSAID Use and the Risk of Hospitalization for First Myocardial Infarction in the General Population: A Nationwide Case-control Study from Finland; European Heart Journal; July 2006; Vol. 27; No. 14; pp. 16567-1663.

- Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, Hildebrand P, Tschannen B, Peter M Villiger PM, Egger M; Cardiovascular Safety of Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs: Network meta-analysis; British Medical Journal; January 11, 2011; Vol. 342; Article c7086.

- Editorial: Cardiovascular safety of NSAIDs; British Medical Journal; January 11, 2011; Vol. 342; Article c6618.

- Olsen AMS, Fosbol E, Lindhardsen J, Folke F, Charlot M, Selmer C; Duration of Treatment with Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Impact on Risk of Death and Recurrent Myocardial Infarction in Patients With Prior Myocardial Infarction: A Nationwide Cohort Study; Circulation; May 21, 2011; Vol. 123; No. 20: pp. 2226-2235.

- Krijthe BP, Heeringa J, Hofman A, Franco OH, Stricker BH; Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of atrial fibrillation: A population-based follow-up study; British Medical Journal Open; April 8, 2014; Vol. 4; No. 4; e004059.

- Breitner JCS, Haneuse A, Walker R, Dublin S, Crane PK, Gray SL, Larson EB; Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease with Prior Exposure to NSAIDs in an Elderly Community-based Cohort; Neurology; June 2, 2009; Vol. 72; No. 22; pp. 1899-1905.

- Curhan SG, Eavey R, Shargorodsky J, Curhan GC; Analgesic Use and the Risk of Hearing Loss in Men; The American Journal of Medicine; March 2010; Vol. 123; No. 3; pp. 231-237.

- Gleason JM, Slezak JM, Jung H, Reynolds K, van den Eeden SH, Haque R, Quinn VP, Loo RK, Jacobsen SJ; Regular Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Use and Erectile Dysfunction; Journal of Urology; April 2011; Vol. 185; pp. 1388-1393.

- Kristensen DM, Desdoits-Lethimonier C, Mackey AL, and 16 more; Ibuprofen Alters Human Testicular Physiology to Produce a State of Compensated Hypogonadism; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS, USA); January 23, 2018; Vol. 114; No. 4; pp. E715-E724.

- Lindsay SE, MD, Philipp T, Ryu WHA, Wright C, Yoo J; Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs in the Acute Post-operative Period Are Associated with an Increased Incidence of Pseudarthrosis, Hardware Failure, and Revision Surgery Following Single-level Spinal Fusion; Spine; August 1, 2023; Vol. 48; No. 15; pp. 1057–1063.

- Alemany S, Avella?Garcia C, Liew Z, Garcia?Esteban R, and 22 more; Prenatal and Postnatal Exposure to Acetaminophen in Relation to Autism Spectrum and Attention?deficit and Hyperactivity Symptoms in Childhood: Meta?analysis in Six European Population?based Cohorts; European Journal of Epidemiology; October 2021; Vol. 36; No. 10; pp. 993-1004.

- Bauer AZ, Swan SH, Kriebel D, Liew Z, Taylor HS, Bornehag CG, Andrade AM, Olsen J, Jensen RH, Mitchell RT, Skakkebaek NE, Jégou B, Kristensen DM: Paracetamol [acetaminophen] Use During Pregnancy: A Call for Precautionary Action: Nature Reviews Endocrinology; December 2021; Vol. 17; No. 12; pp. 757-766.

- Khan FY, Kabiraj G, Ahmed MA, Adam M, Mannuru SP, Ramesh V, Shahzad A, Chaduvula P, Khan S; A Systematic Review of the Link Between Autism Spectrum Disorder and Acetaminophen: A Mystery to Resolve; Cureus; July 18, 2022; Vol. 14; No. 7; Article e26995.

- Giles LGF, Muller R; Chronic Spinal Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation; Spine; July 15, 2003; Vol. 28; No. 14; pp. 1490-1502.

- Maroon JC, Bost JW; Omega-3 Fatty Acids (fish oil) as an Anti-inflammatory: An Alternative to Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs for Discogenic Pain; Surgical Neurology; April 2006; Vol. 65; pp. 326–331.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-540.

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults; Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Fenton JJ, Fang SY, Ray M, Kennedy J, Padilla K, Amundson R, Elton D, Haldeman S, Lisi AJ, Sico J, Wayne PM, Romano PS; Longitudinal Care Patterns and Utilization Among Patients with New-Onset Neck Pain by Initial Provider Specialty; Spine; October 15, 2023; Vol. 48; No 20; pp. 1409–1418.

- Mooney V; Where Is the Pain Coming From?; Spine; October 1987; Vol. 12; No. 8; pp. 754-759.

- Panjabi MM: A Hypothesis of Chronic Back Pain: Ligament Sub-failure Injuries Lead to Muscle Control Dysfunction; European Spine Journal; May 2006; Vol. 15; No. 5; pp. 668-676.

- Bogduk N; On Cervical Zygapophysial Joint Pain After Whiplash; Spine; December 1, 2011; Vol. 36; No. 25S; pp. S194–S199.

- MacVicar J, MacVicar AM, Bogduk N; The Prevalence of “Pure” Lumbar Zygapophysial Joint Pain in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain; Pain Medicine; February 4, 2021; Vol. 22; No.1; pp. 41–48.

- Sperry MM, Ita ME, Kartha S, Zhang S, Yu YH, Winkelstein B; The Interface of Mechanics and Nociception in Joint Pathophysiology: Insights form te Facet and Temporomandibular Joints; Journal of Biomechanical Engineering; February 2017; Vol. 139; No. 2; pp. 0210031-02100313.

- Muller R, Giles LGF; Long-Term Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial Assessing the Efficacy of Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation for Chronic Mechanical Spinal Pain Syndromes; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; January 2005; Vol. 28; No. 1; pp. 3-11.

- Keeney BJ, Fulton-Kehoe D, Turner JA, Wickizer TM, Chan KCG; Franklin GM; Early Predictors of Lumbar Spine Surgery after Occupational Back Injury: Results from a Prospective Study of Workers in Washington State; Spine; May 15, 2013; Vol. 38; No. 11; pp. 953-964.

- Kim S, Kim G, Kim H, Park J, Lee J, and nine more; Safety of Chuna Manipulation Therapy in 289,953 Patients with Musculoskeletal Disorders: A Retrospective Study; Healthcare; February 2, 2022; Vol. 10; No. 2; Article 294.

- Chu E, Trager RJ, Lee L, Niazi IK; A Retrospective Analysis of the Incidence of Severe Adverse Events Among Recipients of Chiropractic Spinal Manipulative Therapy; Scientific Reports; January 23, 2023; Vol. 13; No. 1; Article 1254.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”