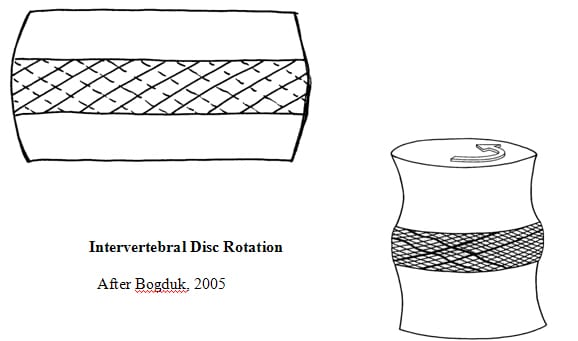

This month we take a close look at manipulation of the joints of the lumbar spine and the relationship to Lumbar disc protrusion. Often lumbar manipulation involves some degree of rotation. Lumbar spine manipulations that are primarily rotational in nature are often discouraged as it is assumed that such maneuvers are associated with an increased risk of injury to the annulus of the intervertebral disc. The traditional caution pertaining to such manipulations is based upon an understanding of the anatomy of the annulus. The collagen fibers that comprise the annulus of the disc are arranged in layers, and each layer is crossed in opposite directions. During disc rotational movements, half of the annular collagen fibers become tense, and the other half become lax. Consequently, it is argued that rotational stress applied to the annulus of the disc is resisted by only half of the annular collagen fibers, the half that become tense. In essence, it is argued that the disc is operating at only half strength during rotationally applied stress, increasing its vulnerability to injury.

Crossed Annular Fibers of the Intervertebral Disc

Despite these academic arguments, there is contrary evidence pertaining to the dangers of rotational manipulations of the lumbar spine. In fact, there is evidence that rotational manipulations are safe when applied by an appropriately trained provider. Additionally, there is evidence that lumbar spine rotational manipulations are effective in the treatment of low back pain, including the management of disc herniation.

In 1954, RH Ramsey, MD published a study titled:

Conservative Treatment of Intervertebral Disk Lesions

Dr. Ramsey’s study appeared in the Instructional Course Lectures of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons. Dr. Ramsey states:

“The conservative management of lumbar disk lesions should be given careful consideration because no patient should be considered for surgical treatment without first having failed to respond to an adequate program of conservative treatment.”

“If after a fair trial of conservative treatment, the pain and disability continue and the symptoms are of sufficient gravity to warrant surgery, the patient is advised that he should be operated upon and the offending disk lesion should be removed.”

Dr. Ramsey advocated the following sequence of conservative treatment before considering a surgical option for patients with low back pain:

1) Varying degrees of rest:

Rest is most beneficial in acute cases and less beneficial in chronic cases.

It is important to curtail non-occupational activities such as athletics or more strenuous home hobbies. “Prolonged sitting, standing or walking should usually be stopped.”

2) Manipulation.

3) Local heat.

4) A firm bed:

“Most patients with low back pain on a mechanical basis rest much better on a bed which does not sag in the middle.”

5) A low back support:

“The patient is advised to wear the support during the day and also in the evening at anytime he or she is going to be up and more active.”

6) Instruction in the avoidance of strain:

“The patient should be advised to avoid all activities that aggravate his pain. He is especially warned about heavy lifting.”

Under some circumstances, it may be necessary for the patient to change his occupation.

“All strenuous athletic pursuits should be stopped temporarily.”

7) Postural exercises:

These should be both strengthening and stretching exercises.

8) Medication:

“Fairly large doses of the vitamin B Complex have proved beneficial to many patients.”

9) Weight control:

“Obesity definitely predisposes the patient to painful back conditions and such patients should be encouraged to reduce to a normal weight.”

10) Improvement in general health.

Pertaining to manipulation, Dr. Ramsey makes the following comments:

“From what is known about the pathology of lumbar disk lesions, it would seem that the ideal form of conservative treatment would theoretically be a manipulative closed reduction of the displaced disk material.”

“Many forms of manipulation are carried out by orthopaedic surgeons and by cultists and this form of treatment will probably always be a controversial one.”

“We limit the use of manipulation almost entirely to those patients who do not seem to be responding well to non-manipulative conservative treatment and who are anxious to have something else done short of operative intervention.”

“The method we use is relatively simple and can be done with or without anesthesia. It is more likely to be effective with anesthesia because the muscle relaxation permits greater motion by manipulation.”

“The patient lies on his side on the edge of the table facing the surgeon and the leg that is up is allowed to drop over the side of the table, tending to swing the up-side of the pelvis forward. The arm that is up is allowed to drop back behind the patient, tending to pull the shoulder back. The surgeon then places one hand on the patient’s shoulder and his opposite forearm on the patient’s iliac crest. Simultaneously, the shoulder is thrust suddenly back, rotating the torso in one direction while the iliac crest is thrust down and forward, rotating the pelvis in the opposite direction. This gives the lumbar spine a twist that frequently causes an audible and palpable crunch. This procedure is then repeated with the patient on his other side. The patient is then turned on his back and his hips and knees are hyperflexed sufficiently to forcibly flex the lumbar spine which tends to open up the disk spaces posteriorly.”

“The patient should be cautioned beforehand that forceful manipulation may possibly make his symptoms worse although many patients will get marked relief.”

Dr. Ramsey clearly defines the procedure as a lumbar spine manipulation. It is also clear the manipulation is rotational in nature, describing it using the term “twist.” Additionally he notes that the manipulation is “forceful” and associated with an “audible and palpable crunch.” Although he cautions that the manipulation may make the patient worse, “many patients will get marked relief.”

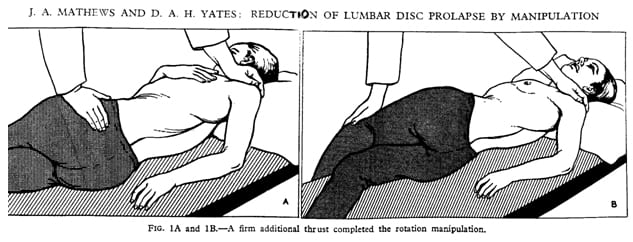

Fifteen years later (in 1969), physicians JA Mathews and DAH Yates from the Department of Physical Medicine, St. Thomas’ Hospital, London, published a study titled:

Reduction of Lumbar Disc Prolapse by Manipulation

This study by Drs. Mathews and Yates appeared in the September 20, 1969 issue of the British Medical Journal. These authors evaluated a number of patients that presented with an acute onset of low back and buttock pain who did not respond to rest. Diagnostic epidurography showed a clinically relevant small disc protrusion, along with antalgia and positive lumbar spine nerve stretch tests. These patients were then treated with long-lever rotation manipulations of the lumbar spine, using the shoulder and iliac crest as levers. These lumbar spine manipulations were clearly accompanied with a thrust maneuver. The manipulations were repeated until abnormal symptoms and signs had disappeared. Following the manipulations there was resolution of signs, symptoms, antalgia, and reduction in the size of the protrusions.

The following drawing and description of the rotation manipulation was included in their study:

REDUCTION OF LUMBAR DISC PROLAPSE BY MANIPULATION

The caption below this drawing said:

“A firm additional thrust completed the rotation manipulation.”

Important comments from Drs. Mathews and Yates from this study include:

“Manipulation of the lumbar spine has been used as an empirical treatment of low backache since antiquity. The persistence and popularity of this type of treatment was based on the clinical impression that it is beneficial.”

“The frequent accompaniment of acute onset low back pain by spinal deformity suggests a mechanical factor, and the accompanying abnormality of straight-leg raise or femoral stretch test suggests that the lesion impinges on the spinal dura matter of the dural nerve sheaths.”

“The lumbar spine was rotated away from the painful side to the limit of its range, the buttock or thigh of the painful side being used as a lever; a firm additional thrust was made in the same direction. This manoeuver was repeated until abnormal symptoms and signs had disappeared, progress being assessed by repeated examination.”

“Rotation manipulations apply torsion stress throughout the lumbar spine. If the posterior longitudinal ligament and the annulus fibrosus are intact, some of this torsion force would tend to exert a centripetal force, reducing prolapsed or bulging disc material.”

“The results of this study suggest that small disc protrusions were present in patients presenting with lumbago and that the protrusions were diminished in size when their symptoms had been relieved by manipulations.”

These authors concluded “it seems likely that the reduction effect [of the disc protrusion] is due to the manipulating thrust used.”

Once again, this article by Mathews and Yates clearly describe and draw the manipulations used, including the words “forceful,” “thrust,” and “rotation.” An interesting explanation for the successful treatment as well as the reduction in the size of the protrusion is uniquely linked to the rotational component of the manipulation: rotation tightens up intact aspects of the annular ring, pulling the nuclear protrusion towards the center and away from the nervous system.

In another study published in 1969, BC Edwards compared the effectiveness of heat/massage/exercise to spinal manipulation in the treatment of 184 patients that were grouped according to the presentation of back and leg pain, as follows:

Group | Treatment | Acceptable Outcome |

Central Low Back Pain Only | heat/massage/exercise | 83% |

spinal manipulation | 83% | |

Pain Radiation to Buttock | heat/massage/exercise | 70% |

spinal manipulation | 78% | |

Pain Radiation Down Thigh to Knee | heat/massage/exercise | 65% |

spinal manipulation | 96% | |

Pain Radiation down Leg to Foot | heat/massage/exercise | 52% |

spinal manipulation | 79% |

This study by Edwards was published in the Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. The authors of the text that is perhaps the most authoritative text on spinal clinical biomechanics, White and Panjabi’s Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine, subsequently reviewed it in 1990. The authors are:

Augustus A. White, MD, DMed Sci

Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at Harvard Medical School

Orthopedic Surgeon-in-Chief at Beth Israel Hospital in Boston

Manohar M. Panjabi, PhD

Professor of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation and Mechanical Engineering

Director of Biomechanics Research

Yale University School of Medicine

Drs. White and Panjabi make the following points pertaining to the Edwards article:

“A well-designed, well executed, and well-analyzed study.”

In the group with central low back pain only, “the results were acceptable in 83% for both treatments. However, they were achieved with spinal manipulation using about one-half the number of treatments that were needed for heat, massage, and exercise.”

In the group with pain radiating into the buttock, “the results were slightly better with manipulation, and again they were achieved with about half as many treatments.”

In the groups with pain radiation to the knee and/or to the foot, “the manipulation therapy was statistically significantly better,” and in the group with pain radiating to the foot, “the manipulative therapy is significantly better.”

“This study certainly supports the efficacy of spinal manipulative therapy in comparison with heat, massage, and exercise. The results (80 – 95% satisfactory) are impressive in comparison with any form of therapy.”

It is usual for pain that travels further down an extremity to be associated with greater compression, or a larger disc protrusion. In this study by Edwards, manipulation worked excellently in patients with leg pain radiation, especially when compared to heat/massage/exercise. An explanation for this finding, as expressed by Mathews and Yates above, is that in such cases manipulation is superior because of its ability to move the protrusion away from the nervous system and closer to the midline.

In 1977, the third edition of Orthopaedics, Principles and Their Applications was published. The author, Samuel Turek, MD (d. 1986), was a Clinical Professor, Department of Orthopedics and Rehabilitation at the University of Miami School of Medicine. His text encompasses 1,574 pages. In the section pertaining to the protruded disc, Dr. Turek makes the following observations:

Treatment of Intervertebral Disc Herniation With Manipulation

“Manipulation. Some orthopaedic surgeons practice manipulation in an effort at repositioning the disc. This treatment is regarded as controversial and a form of quackery by many men. However, the author has attempted the maneuver in patients who did not respond to bed rest and were regarded as candidates for surgery. Occasionally, the results were dramatic.

Technique. The patient lies on his side on the edge of the table facing the surgeon, and the uppermost leg is allowed to drop forward over the edge of the table, carrying forward that side of the pelvis. The uppermost arm is placed backward behind the patient, pulling the shoulder back. The surgeon places one hand on the shoulder and the other on the iliac crest and twists the torso by pushing the shoulder backward and the iliac crest forward. The maneuver is sudden and forceful and frequently is associated with an audible and palpable crunching sound in the lower back. When this is felt, the relief of pain is usually immediate. The maneuver is repeated with the patient on the opposite side.”

“The patient should be cautioned beforehand that the manipulation may make his symptoms worse and that this is an attempt to avoid surgery.”

The manipulation maneuver described by Dr. Turek is the classic description of the rotational manipulation of the lumbar spine. Dr. Turek uses the word “twists” to describe the rotational maneuver. Dr. Turek’s description supports the writings and outcomes of Dr. Ramsey from 1954, and importantly, is in agreement with the other authors above. Dr. Turek’s comments are in the aspect of his book pertaining to the treatment of the protruded intervertebral disc.

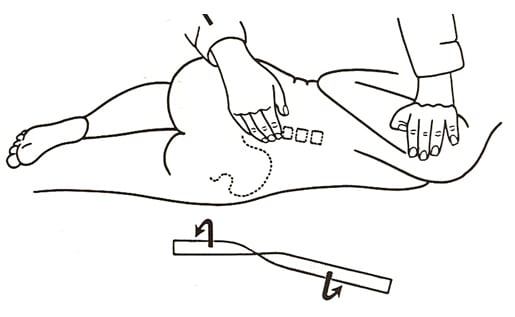

In February 1987, physicians Paul Pang-Fu Kuo and Zhen-Chao Loh published an important study pertaining to lumbar disc protrusions and rotary spinal manipulation, titled:

Treatment of Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Protrusions

by Manipulation

Their article appeared in the prestigious journal Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research. Drs. Paul Pang-Fu Kuo and Zhen-Chao Loh are from the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Shanghai Second Medical College, and Chief Surgeon, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Rui Jin Hospital, Shanghai, China. They note that manipulation has been used in Chinese healthcare for thousands of years, and by the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD), “manipulation was fully established and became a routine for the treatment of low back pain.”

In their study, they performed a series of eight manipulations on 517 patients with protruded lumbar discs and clinically relevant signs and symptoms. Their outcomes were quite good, with 84% achieving a successful outcome and only 9% not responding. Only 14 % suffered a reoccurrence of symptoms at intervals ranging from two months to twelve years.

In the photographic depiction of the eight procedures used by these authors, one is clearly similar to a side posture rotary manipulation of the lumbar spine that is similar to the drawing by Mathews and Yates above. This is accompanied with the following description:

“The patient is placed on the sound side first with the hip and knee of the painful side flexed and the sound side straight. The operator rests one hand in front of the shoulder and the other hand on the buttock. By simultaneously pulling the shoulder backwards and pushing the buttock forwards, a snap or click can usually be heard or felt. This manipulation may then be repeated on the other side as required.”

Based upon their results, Drs. Kuo and Loh make these statements:

“Manipulation of the spine can be effective treatment for lumbar disc protrusions.”

“Most protruded discs may be manipulated. When the diagnosis is in doubt, gentle force should be used at first as a trial in order to gain the confidence of the patient.”

Drs. Kuo and Loh stress that rotation “is the key maneuver of the manipulation.” Consistent with others (above), they suggest that the rotational stresses applied to the annulus of the disc actually reposition the protrusion away from the nervous system and back towards the center of the disc. Supporting statements include:

“Manipulation usually begins with preparatory movements of the vertebral joints to their extreme and then rotation is carried out.”

“During manipulation a snap may accompany rotation. Subjectively it has dramatic influence on both patient and operator and is thought to be a sign of relief.”

“If derangement of the facets or subluxation of the posterior elements near the protruded disc occurs, the rotation may have caused reduction, giving remarkable relief.”

“Gapping of the disc on bending and rotation may create a condition favorable for the possible reentry of the protruded disc into the intervertebral cavity, or the rotary manipulation may cause the protruded disc to shift away from pressing on the nerve root.”

In terms of applying manipulation, Drs. Kuo and Loh indicate “practice is necessary to become proficient in spinal manipulation techniques,” and “expertise plays an important role in the success of manipulation.” The manipulation of disc protrusions should be performed only by trained experts. Additionally, manipulation is contraindicated if the patient is suffering from incontinence or paraplegia.

In 1993, chiropractor J. David Cassidy, chiropractor Haymo Thiel, and physician William Kirkaldy-Willis published a “Review Of The Literature” article titled:

Side Posture Manipulation For

Lumbar Intervertebral Disk Herniation

These authors are from the Department of Orthopaedics, Royal University Hospital, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, and their article appeared in the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics.

In their article, these authors cite studies on human cadavers that show the annulus of the disc is quite resistant to rotational stresses. Specifically, a normal disc did not show failure until 22.6° of rotational stress, and a degenerated disc could withstand and average of 14.3° of rotational stress. They therefore conclude “torsional failure of the lumbar disk first requires fracture of the posterior joints” before there is any annular tearing.

When performing rotational manipulation in the management of lumbar disc herniation, these authors suggest that it is wise to begin with mobilization prior to performing manipulation to assess the patients responses. Additionally, they state that if positioning increases leg pain, “one should not proceed to manipulation at that particular session.”

Based upon their review of the literature and their own experiences, these authors state:

“The treatment of lumbar disk herniation by side posture manipulation is not new and has been advocated by both chiropractors and medical manipulators.”

“The treatment of lumbar intervertebral disk herniation by side posture manipulation is both safe and effective.”

Rotational Manipulation

After Cassidy, Thiel, and Kirkaldy-Willis

The biomechanical studies that best support the safety of rotation stress to the intervertebral disc have been completed by Adams, Hutton, and Dolan. In 1981, MA Adams, PhD, and WC Hutton, MSc, published an important study in the journal SPINE, titled:

The Relevance of Torsion to the

Mechanical Derangement of the Lumbar Spine

In their cadaver experiments, these authors noted that the limit of spinal segmental rotation was not created by the disc, but rather by the facet joint. During rotational stress, the compression facet is the first structure to yield at the limit of torsion, and this occurs after about 1-2° of rotation. “Much greater angles are required to damage the intervertebral disc, so torsion seems unimportant in the etiology of disc degeneration and prolapse.” Important statements in this article include:

“Because of the protection offered by the compression facet, the intervertebral disc is subjected to relatively small stresses and strains in the physiologic range of torsion. By the time the facets are damaged, the disc is rotated only about one-third to one-tenth of its maximum angle and is bearing a small fraction of the torque required to rupture it.”

“Except in cases of extreme trauma and as a sequel to crushing of the apophyseal joints, axial rotation can play no major part in the mechanical derangement of the intervertebral disc in life.”

Two years later, in 1983, Adams and Hutton publish additional cadaver studies in journal Spine, titled:

The Mechanical Function of the Lumbar Apophyseal Joints

Based upon their experiments, they conclude that the facet joints “prevent excessive movement from damaging the discs: the posterior annulus is protected in torsion by the facet surfaces and in flexion by the capsular ligaments.” They note that the facets only allow at most 2° of rotation, and also note that the disc will completely recover from all rotational stresses that are less then 3°. Specific statements include:

“In flexion, as in torsion, the apophyseal joints protect the intervertebral disc.”

“The function of the lumbar apophyseal joints is to allow limited movement between vertebrae and to protect the discs from shear forces, excessive flexion, and axial rotation.”

Lastly, in 1995, Adams and Dolan published a study in Clinical Biomechanics titled:

Recent Advances in Lumbar Spinal Mechanics

and their Clinical Significance

Once again, these authors note that rotational loading of a spinal motor unit will always damage the facet joints “long before the disc.” If the facet joints are removed, rotational forces will damage the disc if subjected to rotational loads between 10-20°.

These authors also note “severely degenerated discs cannot be made to prolapse, presumably because the nucleus is too fibrous to exert a hydrostatic pressure on the annulus.”

CONCLUSIONS

The information presented here indicates that for most patients suffering from a lumbar disc prolapse, rotational manipulation of the lumbar spine is statistically quite safe and often quite effective. Because there are some risks and because effective manipulation requires training and experience, such manipulation should only be performed by a trained expert.

References

Bogduk N; Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine; Fourth edition, Elsevier, 2005.

Ramsey RH; Conservative Treatment of Intervertebral Disk Lesions; American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, Instructional Course Lectures; Volume 11, 1954, pp.118-120.

Mathews JA and Yates DAH; Reduction of Lumbar Disc Prolapse by Manipulation; British Medical Journal September 20, 1969, No. 3, 696-697.

Edwards BC; Low back pain and pain resulting from lumbar spine conditions: a comparison of treatment results; Australian Journal of Physiotherapy; 15:104, 1969.

White AA, Panjabi MM; Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine; Second edition, JB Lippincott Company, 1990.

Turek S; Orthopaedics, Principles and Their Applications; JB Lippincott Company; 1977; page 1335.

Kuo PP and Loh ZC; Treatment of Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Protrusions by Manipulation; Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research. No. 215, February 1987, pp. 47-55.

Cassidy JD, Thiel HW, Kirkaldy-Willis WH; Side posture manipulation for lumbar intervertebral disk herniation; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; February 1993;16(2):96-103.

Adams MA and Hutton WC, MSc; The Relevance of Torsion to the Mechanical Derangement of the Lumbar Spine; Spine; Volume 6, Number 3, May/June 1981, pp. 241-248

Adams MA and Hutton WC, MSc; The Mechanical Function of the Lumbar Apophyseal Joints; Spine; Volume 8, Number 3, April 1983, pp. 327-330.

Adams MA and Dolan P; Recent advances in lumbar spinal mechanics and their clinical significance; Clinical Biomechanics; Volume 10, Number 1, 1995, pp. 3-19.