BACKGROUND INFORMATION FROM DAN MURPHY

- All pain has an inflammatory component. In his 2007 article, Omoigui, concludes:

“The origin of all pain is inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

“Irrespective of the type of pain, whether it is acute or chronic pain, peripheral or central pain, nociceptive or neuropathic pain, the underlying origin is inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

“Activation of pain receptors, transmission and modulation of pain signals, neuroplasticity and central sensitization are all one continuum of inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

“Irrespective of the characteristic of the pain, whether it is sharp, dull, aching, burning, stabbing, numbing or tingling, all pain arises from inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

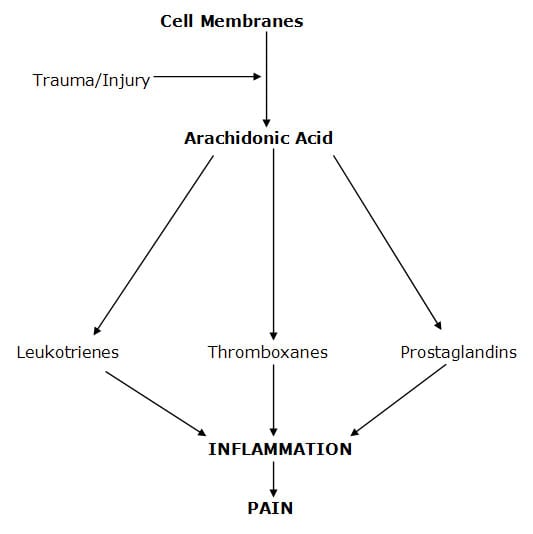

- Post-traumatic inflammation is often the consequence of the membrane release of arachidonic acid fat cascading into the pro-inflammatory hormone prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). In his 2010 article, Maroon states:

“A major component of the inflammatory pathway is called the arachidonic acid pathway because arachidonic acid is immediately released from traumatized cellular membranes.”

Cell membrane trauma releases arachidonic acid. Arachidonic acid is then transformed into the pro-inflammatory hormones prostaglandins and thromboxanes through the enzymatic action of cyclooxygenase.

This is why omega-6/omega-3 fatty acid balancing is an important clinical strategy in the management of patients suffering from pain syndromes (Boswell, 2006).

- Inflammation alters the pain threshold and increases pain perception (Omoigui, 2007; Boswell, 2006; Maroon, 2006; Cleland, 2006; Goldberg 2007; Maroon, 2010). In 2007, Omoigui states:

The unifying Law of Pain indicates that there is an inflammatory soup of biochemical mediators that are present in all pain syndromes.

- The resolution of inflammation is fibrosis or scar tissue (Manjo, 2004). In 2004, Manjo states:

“After a day or two of acute inflammation, the connective tissue—in which the inflammatory reaction is unfolding—begins to react, producing more fibroblasts, more capillaries, more cells—more tissue. In other words, granulation tissue arises from normal connective tissue, but it cannot be mistaken for normal connective tissue, because its fibroblasts are plump and activated.”

“Fibrosis means an excess of fibrous connective tissue. It implies an excess of collagen fibers, with a varying mixture of other matrix components. It can be a local phenomenon, as an end result to chronic inflammation and of wound healing.”

“When fibrosis develops in the course of inflammation it may contribute to the healing process.” “By contrast, an excessive or inappropriate stimulus can produce severe fibrosis and impair function.”

“Why does fibrosis develop? In most cases the beginning clearly involves chronic inflammation. Fibrosis is largely secondary to inflammation.”

- Fibrotic granulation tissue is capable of maintaining an inflammatory response long after the completion of the healing process, a component of chronic pain (Cyriax, 1982). In 1982, Cyriax states:

“Fibrous tissue appears capable of maintaining an inflammation, originally traumatic, as the result of a habit continuing long after the cause has ceased to operate.”

“It seems that the inflammatory reaction at the injured fibers continues, not nearly during the period of healing, but for an indefinite period of time afterwards, maintained by the normal stresses to which such tissues are subject.”

- Tension within the scar granulation tissue initiates remodeling, reducing inflammation. [Supports the need for early persistent mobilization and chiropractic adjustments]. Once again, in 1982 Cyriax states:

“Tension within the granulation tissue lines the cells up along the direction of stress. Hence, during the healing of mobile tissues, excessive immobilization is harmful. It prevents the formation of a scar strong in the important direction by avoiding the strains leading to due orientation of fibrous tissue and also allows the scar to become unduly adherent, e.g. to bone.”

••••••••••

Americans eat a lot of fat. This is important in a trauma clinical practice because one particular type of fat is linked to both acute and chronic pain. In fact, this fat was the central theme of the 1982 Nobel Prize in Medicine/Physiology, which pertained to pain.

Our bodies have somewhere around 75 trillion cells. The cell membranes are composed primarily of fat, and it is the fat that we habitually eat. Trauma/injury to tissues disrupts the cell membranes, releasing the fat and activating enzymes that metabolize those fats (Maroon, 2010).

There is a type of dietary fat that is linked to inflammation and pain. If people eat this pro-inflammatory pain producing fat, then it is that fat that is released as a consequence of trauma/injury. This fat is not a saturated fat. It is a poly-unsaturated fatty acid called arachidonic acid. Arachidonic acid is an omega-6 fat. Our bodies have enzymes that convert arachidonic acid into pro-inflammatory hormones (leukotrienes, thromboxanes, prostaglandins); and these pro-inflammatory hormones are linked to pain (Omoigui, 2007; Boswell, 2006; Maroon, 2006; Cleland, 2006; Goldberg 2007; Maroon, 2010).

The primary American source of dietary arachidonic acid is eating meat. Meat is not bad per se. Meat becomes bad when the animal is fed junk food that makes it fat and sick. Economically, our food animals are fed the food that is most fattening. That’s because they are sold by the pound. Fatter animals are worth more in the marketplace. Our food animals are proven to become really fat on a diet of corn and/or soybeans.

Of course, fattening animal feed is a poor economic choice unless it is also cheap feed. In today’s political environment, the cheapest feed is the food that is subsidized by the taxpayers; and it makes so much sense: lobbying our politicians to use taxpayer dollars to grow corn and soybeans creates a win-win situation for all, cheap meat (this is sarcasm, as noted below).

Meat, a source of complete proteins, historically was an expensive and therefore rare commodity (at least since the Agricultural Revolution, beginning about 10,000 years ago). Animals become big and fat on a corn/soybean diet, and if the taxpayers subsidize these crops, the corn and soybeans also become much cheaper. By extension, the taxpayers (and the Chinese, or whoever is buying our debt) are subsidizing the cost of meat, making it so that nearly all Americans can afford to eat meat daily (if they choose to do so).

Recent evidence suggests that nearly 100% of our chickens and 93% of our cows are exclusively fed corn (USA Today, 2008). A major source of feed for our farmed fish is soybeans (Greenberg, 2010). Sadly, when these food animals are fed corn and/or soybeans, they have enzymes that convert the fat found in these crops (linoleic acid) into the pro-inflammatory hormone precursor fat, arachidonic acid.

These pro-inflammatory fats are in the omega-6 family. One hundred years ago, the amount of omega-6 fats consumed by Americans was about 2 pounds per year. Today, as a consequence of politics and economics, consumption of omega-6 fats has increased to about 25 pounds (Boswell, 2006). In contrast, the quantity of anti-inflammatory omega-3 fats in our diets had decreased substantially.

Paleolithic humans evolved with a ratio of omega-6/omega-3 fats of about 1/1; the average modern ratio is about 25/1 (Boswell, 2006). This means that the average American is prone to pain syndromes as a consequence of dietary choices and habits. At any given moment, 28% of Americans are suffering from pain (Krueger, 2008); the omega-6/omega-3 ratio is critical. The sarcastic downside from the win-win of cheap fat meat is that it predisposes the consumers, Americans, to pain syndromes. This has resulted in Americans consuming more than 70 million nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) prescriptions every year; and 30 billion over-the-counter NSAID tablets are sold annually (Maroon, 2006). The cost is $17 billion per year (Krueger, 2008). Michael Pollan states in his 2008 book In Defense of Food “The billions we spend on anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen is money spent to undo the effects of too much omega-6 in the diet.”

Dietary strategies to rebalance the omega-6/omega-3 ratio have proven to prevent an/or reverse many of these pathological syndromes. Such strategies have proven to be more effective than pain medications about 88% of the time (Maroon, 2006).

••••••••••

This month (August 2011), primary research from the Department of Bioengineering and the Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pennsylvania, provides some of the most important insights into the patho-biomechanics of chronic whiplash injury to date. The study was published in the journal Annals of Biomedical Engineering, and titled (Quinn, 2011):

Detection of Altered Collagen Fiber Alignment in the Cervical Facet Capsule After Whiplash-Like Joint Retraction

The authors review that the cervical facet joint is the primary source of pain in patients with whiplash-associated disorders; yet, most clinical studies show no radiographic or MRI evidence of tissue injury. To evaluate this puzzle, these authors used quantitative polarized light imaging to assess the potential for altered collagen fiber alignment in human cadaveric cervical facet capsule specimens during and after a joint retraction simulating whiplash exposure.

The authors document that the whiplash mechanism involves a retraction event to the facet joint capsular ligaments. Although no evidence of ligament damage was detected during whiplash-like retraction, mechanical and microstructural changes of the facet joint capsular ligaments were identified following these whiplash loadings. The retraction experience produced significant decreases in ligament stiffness and increases in ligament laxity. The strained capsule regions showed altered fiber alignment, “suggesting the altered mechanical function may relate to a change in the tissue’s fiber organization.” The altered capsular ligament fiber alignment occurred without any tears that would classically be identified with diagnostic imaging, including radiographs and/or MRI. Consequently, the authors indicate that whiplash kinematics is a potential cause of microstructural damage that is not detectable using standard clinical imaging techniques.

The authors make these key points:

1) This is the first study that has assessed changes in tissue microstructural organization of the facet capsule following whiplash-like loading.

2) “Whiplash is a common cause of chronic neck pain, and the cervical facet joint has been identified as the site of pain in the majority of these cases.”

3) “Up to 62% of people affected by whiplash injuries report pain lasting 2 years or more after injury.”

4) Facet joint injuries cannot be imaged in most whiplash patients with x-rays or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

5) “The lack of any definitive evidence of facet capsular ligament damage following whiplash, despite the high incidence of facet-mediated pain, suggests radiographic and MRI techniques may lack the resolution or contrast to identify these subtle injuries.”

6) Low-speed rear-end impact collision causes the lower cervical spine to undergo a combination of compression, posterior shear, and extension. “This combination of forces and moments primarily induces a retraction of each vertebra in the posterior direction relative to its adjacent inferior vertebra in the lower cervical spine prior to head-headrest contact.” The facet capsular ligaments are at risk for excessive motion during this vertebral retraction, creating subfailure injuries to the facet capsule. “The facet capsular ligament may sustain partial failures and/or unrecovered deformation during whiplash.”

7) Facet joint injury causes altered collagen fiber organization and facet capsular ligament laxity that may produce persistent pain. “Neither partial failure nor capsule rupture is required to initiate facet-mediated pain, suggesting painful facet joint injuries cannot be identified through traditional load-based or medical imaging techniques.”

8) Prior to ligament visible rupture or mechanical failure, there is an anomalous fiber realignment, which may be used as a marker for subfailure capsule injury.

9) The retraction caused permanent deformation of ground substance materials of the ligament, leading to altered collagen fiber organization. This tissue damage may be sufficient to induce an inflammatory response or nociceptor firing in the ligament.

10) “These findings would suggest that radiographic or MRI diagnostic approaches may lack the resolution to detect the microstructural changes that can occur in the facet capsule without overt capsule rupture after a whiplash exposure.”

11) “Facet joint displacements that produce persistent pain symptoms also induce laxity in the capsular ligament and collagen fiber disorganization.”

12) “The detection of altered fiber alignment and unrecovered strain observed after facet retraction in the current study would suggest that whiplash-like loading may be sufficient to generate facet-mediated pain.”

This study indicates that whiplash injury causes microstructural changes, anomalous fiber realignment and laxity of the facet capsular ligaments. These injuries may cause permanent deformation of ground substance of the ligament, leading to altered collagen fiber organization. These injuries are subfailure in magnitude, but are capable of causing pain and permanent alterations in capsular mechanics. These injuries are not identifiable clinically, with x-ray, or MRI imaging. The tissue damage may be sufficient to induce an inflammatory response and/or nociceptor firing.

The anomalous fiber realignment noted in this study is probably

analogous to the writings of Cyriax when he stated that fibrotic granulation tissue is capable of maintaining an inflammatory response long after the completion of the healing process. This inflammatory granulation tissue becomes a factor in the initiation of chronic pain perception. Consequently, Cyriax also states “…that the scar tissue remains painful whenever tension is put upon it, perhaps for decades.”

This is an important study advancing the understanding of whiplash injury pathoanatomy, yet I believe there is still a missing piece. The authors document post-traumatic anomalous fiber realignment, but they only speculate that it is associated with pain producing inflammation. They offer no evidence for the existence of an actual inflammatory process. Fortunately, the next study does just that.

••••••••••

Clas Linnman (from Harvard Medical School) and an international team of colleagues published a study in April of this year (2011) titled:

Elevated [11C]-D-Deprenyl Uptake in Chronic Whiplash Associated Disorder Suggests Persistent Musculoskeletal Inflammation

These authors note that there are few diagnostic tools for chronic musculoskeletal pain, and especially for whiplash injury. In agreement with Quinn above, they note that structural imaging methods seldom reveal pathological alterations that can account for a patient’s ongoing pain. Therefore, they sought to visualize inflammatory processes in the neck region by means of Positron Emission Tomography (PET) using an inflammatory marker, 11C-D-deprenyl, or DDE. They evaluated 22 patients with chronic pain after a rear impact car accident and 14 healthy controls. The whiplash-injured subjects had pain and reduced motion but no neurological signs.

The whiplash-injured patients displayed significantly elevated inflammatory tracer uptake in the neck, suggesting that whiplash patients have signs of local persistent peripheral tissue inflammation. The authors concluded that inflammation and its associated pain in the periphery could be objectively visualized and quantified with PET using the inflammatory tracer DDE. Key points from this study include:

1) “Chronic musculoskeletal pain syndromes are common, cause extensive individual suffering and place a large burden on health care in society. Yet, pain remains notoriously difficult to visualize and diagnose objectively.”

2) “The pathophysiology of persistent pain is elusive and there is a great need for ways to visualize and quantify pain mechanisms.”

3) In a sub-portion of the population, “whiplash injuries proceed to chronic debilitating pain.”

4) “Structural imaging does not capture on-going biological processes; where as molecular imaging with positron emission tomography (PET) has the potential to visualize such mechanisms.”

5) The authors present evidence that shows “DDE can be used to visualize chronic inflammatory processes.”

6) The site of inflammation “appeared to be localized to adipose tissue surrounding deep cervical muscles.” “The tracer retention observed in fatty regions surrounding deep cervical muscle may indicate that adipose tissue is actively involved in the inflammatory process.”

7) Patients displayed elevated DDE retention in cervical soft tissue, suggesting that localized chronic inflammation is apparent in many chronic pain whiplash patients.

8) “A large subset of patients with chronic pain after a whiplash injury displayed elevated DDE retention, suggestive of persistent peripheral tissue inflammation.”

9) “The possibility to visualize and quantify sites of inflammation in chronic pain may be very useful in diagnosis and treatment monitoring.”

SUMMARY POINTS:

• All pain has an inflammatory component.

• Post-traumatic inflammation is often the consequence of the membrane release of the arachidonic acid fat cascading into pro-inflammatory hormones, including prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). [Therefore omega-6/-3 balancing is an important clinical strategy].

• Inflammation alters the pain threshold and increases pain perception.

• The resolution of inflammation is granulation, fibrosis, or scar tissue.

• Fibrotic granulation tissue is capable of maintaining an inflammatory response long after the completion of the healing process, a component of chronic pain.

• Whiplash trauma can create anomalous fiber alignment and granulation tissue.

• From whiplash, granulation tissue and inflammation occurs as a consequence of subfailure injuries. Therefore, these injuries cannot be visualized with either x-rays or MRI.

• Persistent post-traumatic inflammation has been linked to chronic pain syndrome. This inflammation can be documented with PET using the inflammatory tracer DDE.

• Tension within the scar granulation tissue initiates remodeling, reducing inflammation. This supports the need for early persistent mobilization, exercise, and chiropractic adjustments.

• I believe that anti-inflammatory omega-6/omega-3 balancing is critical in chronic pain management.

Dan Murphy, DC, DABCO

REFERENCES

Omoigui S; The biochemical origin of pain: The origin of all pain is inflammation and the inflammatory response: Inflammatory profile of pain syndromes; Medical Hypothesis; 2007, Vol. 69, pp. 1169 – 1178.

Maroon J, Bost JW, Maroon A; Natural anti-inflammatory agents for pain relief; Surgical Neurological International; December 2010.

Boswell M, Cole EB; American Academy of Pain Management; Weiner’s Pain Management: A Practical Guide for Clinicians; Seventh Edition, 2006, pp.584-585.

Maroon JC, Bost JW; Omega-3 Fatty acids (fish oil) as an anti-inflammatory: an alternative to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for discogenic pain; Surgical Neurology; 65 (April 2006) 326– 331.

Cleland LG, James MJ, Proudman SM; Fish oil: what the prescriber needs to know; Arthritis Research & Therapy; Volume 8, Issue 1, 2006, pp. 402.

Goldberg RJ, Katz J; A meta-analysis of the analgesic effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for inflammatory joint pain; Pain; May 2007, 129(1-2), pp. 210-223.

Manjo G, Joris I; Cells, Tissues, and Disease, Principles of General Pathology; Second Edition; Chapter 13: “Chronic Inflammation: Defense at a Price”; Oxford University Press; 2004.

Cyriax, James, M.D., Orthopaedic Medicine, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, Bailliere Tindall, Vol. 1, (1982).

USA Today, November 12, 2008, quoting Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Greenberg P; Four Fish, The Future of the Last Wild Food; The Penguin Press, New York, 2010.

Krueger AB, Stone AA; Assessment of pain: a community-based diary survey in the USA; Lancet; 2008 May 3;371(9623):1519-25.

Pollan, M; In Defense of Food; 2008, pg. 131.

Quinn KP, Winkelstein BA; Detection of Altered Collagen Fiber Alignment in the Cervical Facet Capsule After Whiplash-Like Joint Retraction; Annals of Biomedical Engineering; August 2011, Vol. 39, No. 8, pp. 2163–2173.

Linnman C, Appel L, Fredrikson M, Gordh T, Soderlund A, Langstrom B, Engler H; Elevated [11C]-D-Deprenyl Uptake in Chronic Whiplash Associated Disorder Suggests Persistent Musculoskeletal Inflammation; Public Library of Medicine (PLoS) ONE; April 6, 2011, Vol. 6 No. 4, pp. e19182.