In this month's issue we're going to touch on area of patient treatment that has undergone enormous leaps and bounds in our understanding over the last decade. An area I will refer to as "Post-Traumatic Soft Tissue Injury".

Even with recent breakthroughs in understanding the physiology of repair (and possibly because of these RECENT breakthroughs) there is a considerable amount of misunderstanding regarding soft tissue injury and its repair.

The most common (almost knee-jerk) misconception is that injured soft tissue will heal in a period of time between four and eight weeks.

Frequently it is claimed that injured soft tissues will heal spontaneously, leaving no long-term residual damage, and that treatment is not required. This type of information is extremely misleading and confusing to both doctor and patient alike.

Published articles and books concerning the healing of injured soft tissues (Oakes 1982; Roy and Irving 1983; Kellett 1986; Buckwalter/Woo 1988, Majno 2004) indicate that the time frame for such healing is approximately one year.

Needless to say the difference between a recovery time of 4-8 weeks and 12 months dramatically impacts both clinical practice and expected outcomes.

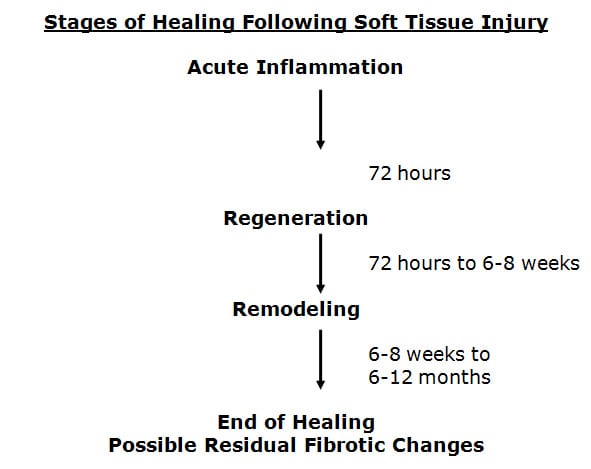

Healing Takes Place In Three Specific Phases. Soft Tissue Healing Phase #1 Acute Inflammatory Phase.

This phase will last approximately 72 hours. During this phase, after the initial injury, an electrical current is generated at the wound, called the "current of injury."

This "current of injury" attracts fibroblasts to the wound (Oschman, 2000).

During this phase there is also initial bleeding and continual associated inflammation of the injured tissues. Because of the increasing inflammatory cascade during this period of time, it is not uncommon for the patient to feel worse for each of the first three days following injury.

Because there is disruption of local vascular supplies, there is insufficient availability of substrate (glucose, oxygen, etc.) to produce large enough quantities of ATP energy to initiate collagen protein synthesis to repair the wound.

After 72 hours following injury, the damaged blood vessels have mended. The resulting increased availability of glucose and oxygen elevates local ATP levels and collagen repair begins by the fibroblasts that accumulated during the acute inflammatory phase.

Soft Tissue Healing Phase #2 Phase Of Regeneration

During the regeneration phase the disruption in the injured muscles and ligaments is bridged. Some references call the regeneration phase the phase of repair, which creates confusion about the timing of healing (Jackson, 1977).

"Repair" connotation is that the process has completed, which, as we well see, is not the case. The fibroblasts manufacture and secrete collagen protein glues that bridge the gap in the torn tissues. This phase will last approximately 6-8 weeks (Jackson, 1977).

At the end of 6-8 weeks, the gap in the torn tissues is more than 90% bridged. Many will erroneously claim this to be the end of healing. However, it clearly is not. There is a third and final phase of healing. This phase is called the phase of remodeling.

Soft Tissue Healing Phase #2 Phase Of Remodeling

The phase of remodeling starts near the end of the phase of regeneration. During the phase of remodeling the collagen protein glues that have been laid down for repair are remodeled in the direction of stress and strain.

This means that the fibers in the tissue will become stronger, and will change their orientation from an irregular pattern to a more regular pattern, a pattern more like the original undamaged tissues.

Proper treatment during this remodeling phase is very necessary if the tissues are to get the best end product of healing. It is during this remodeling phase that the tissues regain strength and alignment. Remodeling takes approximately one year after the date of injury.

It is established that remodeling takes place as a direct byproduct of motion. Chiropractic healthcare puts motion into the tissues in an effort at getting them to line up along the directions of stress and strain, thereby giving a stronger, more elastic end product of healing.

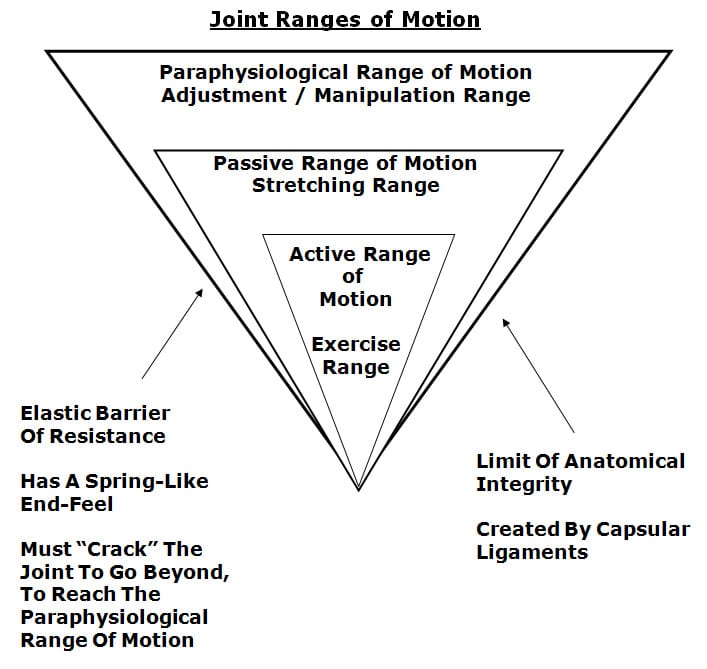

Traditional chiropractic joint manipulation healthcare is directed towards putting motion into the periarticular paraphysiological space.

The concept of paraphysiological joint motion was first described by Sandoz in 1976, and is explained well by Kirkalady-Willis 1983 and 1988, by Kirkalady-Willis/Cassidy 1985, and in the 2004 monograph on Neck Pain (edited by Fischgrund) published by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (see picture).

These discussions clearly show that there is a component of motion that cannot be properly addressed by exercise, massage, etc, and that this component of motion can be properly addressed by osseous joint manipulation.

Therefore, traditional chiropractic osseous joint manipulation adds a unique aspect to the treatment and the remodeling of periarticular soft tissues that have sustained an injury.

There are some problems associated with the healing of injured soft tissues. Microscopic histological studies show that the repaired tissue is different than the original, adjacent, undamaged tissues.

During the initial acute inflammatory phase there is bleeding from the damaged tissues and consequent local inflammation. This progressive bleeding releases increased numbers of fibroblasts into the surrounding tissues.

Chemicals that are released trigger the inflammation response that is noted in cases of trauma. Subsequent to the inflammatory response and to the number of fibrocytes that are released into the tissues, the healing process is really a process of fibrosis.

Fibrosis

In 1975, Stonebrink addresses that the last phase of the pathophysiological response to trauma is tissue fibrosis. Boyd in 1953, Cyriax in 1983, and Majno/Joris in 2004 note that there is tissue fibrosis subsequent to trauma.

This fibrosis of repair subsequent to soft tissue trauma creates problems that can adversely affect the tissues and the patient for years, decades, or even forever.

Fibrosed tissues are functionally different from the adjacent normal tissues. The differences fall into two main categories:

Fibrosis Category 1:

The repaired tissue is weaker and less strong than the undamaged tissues. This is because the diameter of the healing collagen fibers is smaller, and the end product of healing is deficient in the number of crossed linkages within the collagen repair.

Fibrosis Category 2:

The repaired tissue is stiffer or less elastic than the original, undamaged tissues. This is because the healing fibers are not aligned identically to that of the original. Examination range of motion studies will indicate that there are areas of decrease of the normal joint ranges of motion.

In addition, Cyriax notes "fibrous tissue is capable of maintaining an inflammatory response long after the initial cause has ceased to operate."

Since inflammation alters the thresholds of the nociceptive afferent system, physical examinations in these cases will show these fibrotic areas display increased sensitivity, and digital pressure may show hypertonicity and spasm.

This increased sensitivity can be documented with the use of an algometer, which is a device that uses pressure to determine the initiating threshold of pain.

Because the fibrotic residuals have rendered the tissues weaker, less elastic, and more sensitive, the patient will have a history of flare-ups of pain and/or spasm at times of increased use or stress.

These episodes of pain and/or spasm at times of increased use or stress of the once damaged soft tissues is the rule rather than the exception, and a problem that the patient will have to learn to live with.

It is likely that the patient will continue to have episodes of pain and/or spasm for an indefinite period of time in the future. It is probable that the patient will have a need for continuing care subsequent to these episodes of pain and/or spasm.

Consistent with these concepts, a study by Hodgson in 1989 indicated that…

62% of those injured in automobile accidents still have significant symptoms caused by the accident 12 1/2 years after being injured; and that of the symptomatic 62%, 62.5% had to permanently alter their work activities and 44% had to permanently alter their leisure activities in order to avoid exacerbation of symptoms.

One of the conclusions of the article is that these long-term residuals were most likely the result of post-traumatic alterations in the once damaged tissues.

A study by Gargan in 1990 indicated that…

Only 12% of those sustaining a soft tissue neck injury had achieved a complete recovery more than ten years after the date of the accident.

One of the conclusions of this study is that the patient's symptoms would not improve after a period of two years following the injury.

It is established neurologically (Wyke 1985, Kirkalady-Willis and Cassidy 1985) that when a chiropractor adjusts (specific directional spinal manipulation) the joints of the region of pain and/or spasm, that there is a depolarization of the mechanoreceptors that are located in the facet joint capsular ligaments, and that the cycle of pain and/or spasm can be neurologically aborted. This is why many patients feel better after they receive specific joint manipulation from a chiropractor following an episode of increased pain and/or spasm.

What Is The Basis For The Chronic Post-Trauma Pain Syndromes So Many Patients Suffer From?

A good explanation is found from Gunn (1978, 1980, 1989). He refers to this type of pain as supersensitivity.

The supersensitivity type pain is a residual of the scarring or the fibrosis that was created by the injuries sustained in this accident.

The treatment that we give to the patient for the injuries sustained in an accident is really not designed to heal the sprain or strain but rather, to change the fibrotic nature of the reparative process that has left the patient with residuals that are weaker, stiffer, and more sore.

The actual diagnosis for this type of problem is initial sprain/strain injuries of the paraspinal soft tissues with fibrotic residuals subsequent to the fibrosis of repair of once damaged soft tissues that have left these tissues weaker, stiffer, and more sensitive as compared to the original tissues.

The majority of our efforts in the treatment of post-traumatic chronic pain syndrome patients is in dealing with the residual fibrosis of repair and its associated mechanical and neurological consequences.

These residuals to some degree are most probably permanent. The patient will have to learn to deal with the long-term residuals and the occasional episodes of pain and/or spasm.

However, as noted above, occasional specific joint manipulation in the involved areas can neurologically inhibit muscle tone, improve ranges of motion, disperse accumulated inflammatory exudates, and the patient will have less pain and improved function.

The concepts briefly discussed above are frequently not understood or appreciated. There is a tendency for healthcare providers to not properly examine the patient in order to document these regions of tissue fibrosis and its consequent mechanical and neurological consequences and, therefore, to quote Stonebrink, the real problem is missed.

References:

Boyd, William, M.D., Pathology, Lea & Febiger, (1952).

Cyriax, James, M.D., Orthopaedic Medicine, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, Bailliere Tindall, Vol. 1, (1982).

Fischgrund, Jeffrey S, Neck Pain, monograph 27, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2004.

Gargan, MF, Bannister, GC, Long-Term Prognosis of Soft-Tissue Injuries of the Neck, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, September, 1990.

Gunn, C. Chan, Pain, Acupuncture & Related Subjects, C. Chan Gunn,

(1985).

Gunn, C. Chan, Treating Myofascial Pain: Intramuscular Stimulation (IMS) for Myofascial Pain Syndromes of Neuropathic Origin, University of Washington, 1989.

Hodgson, S.P. and Grundy, M., Whiplash Injuries: Their Long-term Prognosis and Its Relationship to Compensation, Neuro-Orthopedics, (1989), 7.88-91.

Kellett, John, "Acute soft tissue injuries-a review of the literature," Medicine and Science of Sports and Exercise, American College of Sports Medicine, Vol. 18 No.5, (1986), pp 489-500.

Kirkaldy-Willis, W.H., M.D., Managing Low Back Pain, Churchill Livingston, (1983 & 1988).

Kirkaldy-Willis, W.H., M.D., & Cassidy, J.D.,"Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low-Back Pain," Can Fam Physician, (1985), 31:535-40.

Majno, Guido and Joris, Isabelle, Cells, Tissues, and Disease: Principles of General Pathology, Oxford University Press, 2004.

Oakes BW. Acute soft tissue injuries. Australian Family Physician. 1982; 10 (7): 3-16.

Oschman, James L, Energy Medicine: The Scientific Basis, Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Roy, Steven, M.D., and Irvin, Richard, Sports Medicine: Prevention, Evaluation, Management, and Rehabilitation, Prentice-Hall, Inc. (1983).

Stonebrink, R.D., D.C., "Physiotherapy Guidelines for the Chiropractic Profession," ACA Journal of Chiropractic, (June1975), Vol. IX, p.65-75.

Wyke, B.D., Articular neurology and manipulative therapy, Aspects of Manipulative Therapy, Churchill Livingstone, 1980, pp.72-77.

Woo, Savio L.-Y.,(ed.), Injury and Repair of the Musculoskeletal Soft Tissues, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons,(1988), p.18-21; 106-117; 151-7; 199-200; 245-6; 300-19; 436-7; 451-2; 474-6.